Who was Saint Thomas Aquinas

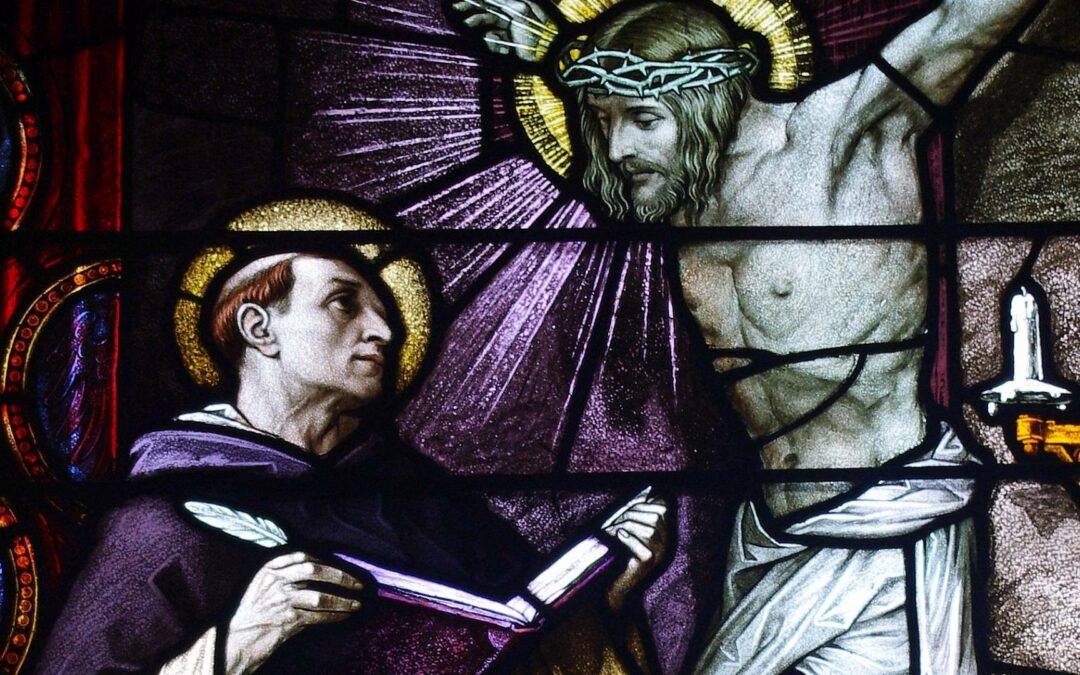

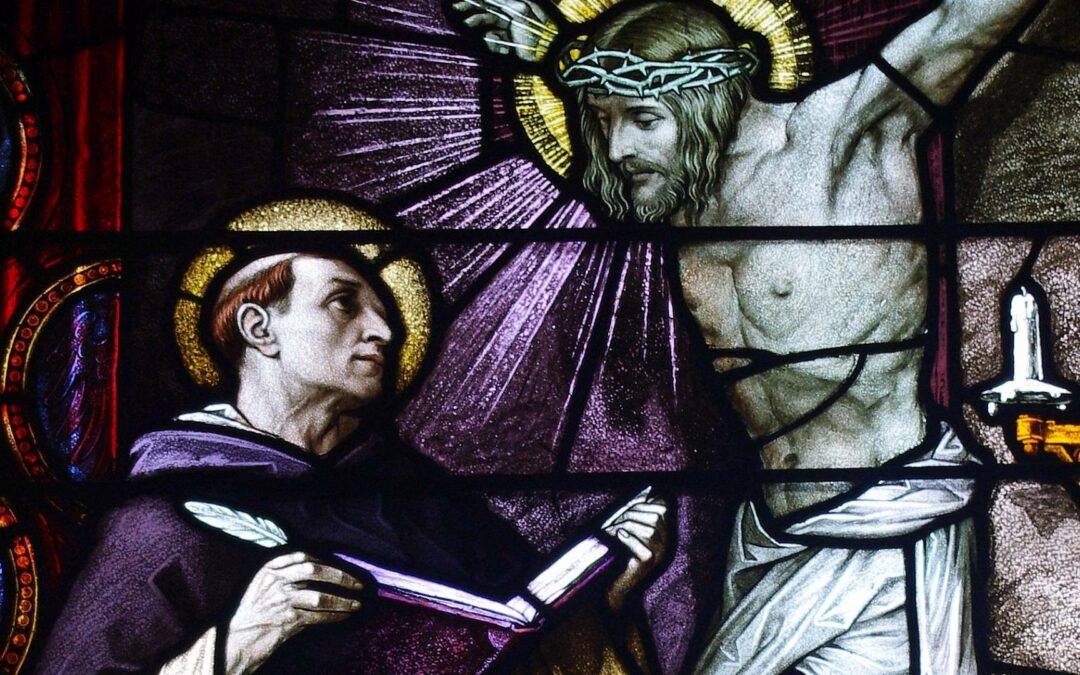

Thomas Aquinas, born around 1225 in Roccasecca, Italy, was a prominent theologian and philosopher who combined theological principles of faith with philosophical principles of reason. He was the youngest of at least nine children in a wealthy family that owned a castle in Roccasecca. As a teenager, he was influenced by the Dominicans, a newly founded order of priests devoted to preaching and learning.

Thomas joined the Dominicans at the age of nineteen and was assigned to Paris for further study. He spent three years in Paris studying philosophy and then moved to Cologne under the supervision of Albert the Great, who became his mentor. Albert’s conviction that the Christian faith could only benefit from a profound engagement with philosophy and science greatly influenced Thomas.

Thomas’s philosophical work is primarily found in the context of his Scriptural theology, and he is known for his so-called ‘five ways’ of attempting to demonstrate the existence of God. He also offered one of the earliest systematic discussions of the nature and kinds of law, including a famous treatment of natural law.

Thomas’s writings on ethical theory are virtue-centred, and he discussed the relevance of pleasure, passions, habit, and the faculty of will for the moral life. He is considered one of the most important theologians in the history of Western civilization, and his model for the correct relationship between theology and philosophy has inspired many.

Thomas died on March 7, 1274, at the Cistercian monastery of Fossanova, near Terracina, Latium, Papal State, Italy. He was canonized by Pope John XXII in 1323 and is honoured as a saint and Doctor of the Church by the Catholic Church.

Aquinas Contribution to the development of Theology and Philosophy

Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) was a Dominican friar, philosopher, and theologian who is considered one of the greatest thinkers in Western intellectual history and a key figure in scholasticism, a medieval philosophical and theological movement.

He is known for his exceptional intellect and scholarship, and his contributions to theology and philosophy continue to be widely recognized and influential today. Aquinas’s most significant work is Summa Theologica, a comprehensive systematic treatise on theology and philosophy that synthesizes and harmonizes the teachings of Aristotle with Christian theology. The work covers a wide range of topics, including the nature of God, ethics, human nature, and the sacraments, and it emphasizes the compatibility of philosophy and theology, rejecting the notion of inherent conflict between them.

Aquinas’ philosophy was marked by his commitment to reason and the integration of faith and reason. He believed that reason and revelation were complementary and that both could lead to a deeper understanding of truth. His approach emphasized the compatibility of philosophy and theology, and he provided rational arguments for the existence of God, known as the “Five Ways,” which presented philosophical justifications for belief in a transcendent Creator. Aquinas also explored the concept of natural law, asserting that there are moral principles rooted in human nature that are accessible through reason. He believed that these moral principles were universal and could be known by all people, regardless of their religious beliefs.

Aquinas’ contributions to theology and philosophy were widely recognized during his lifetime, and his influence continues to be felt today. He is often referred to as the “Doctor Angelicus” and is regarded as one of the church’s greatest theologians and philosophers.

Despite his relatively short life, Aquinas’ extensive writing and profound insights have left an enduring legacy in philosophy, theology, and Christian thought. His teachings remain a cornerstone of Catholic theology, and his approach to the relationship between faith and reason continues to inspire philosophers and theologians around the world.

How did Saint Thomas Aquinas’s ideas influence the development of Christian philosophy?

Saint Thomas Aquinas was known philosopher, and theologian who is considered one of the most important figures in the development of Christian philosophy. His ideas have had a profound influence on the relationship between faith and reason, the philosophy of language, epistemology, metaphysics, natural theology, philosophical anthropology, ethics, and political philosophy. One of Aquinas’ most significant contributions to Christian philosophy is his model for the correct relationship between faith and reason.

He believed that faith and reason were not in conflict but rather complementary, with faith providing a foundation for reason and reason providing a way to understand and defend faith. This approach has been influential in the development of Christian philosophy and theology, and it continues to be a subject of debate and discussion today.

Aquinas’ philosophy of language is also significant, particularly his concept of analogy. He believed that language about God is to be understood analogically, meaning that it is both like and unlike human applications. This concept has been influential in Christian theology and philosophy, and it continues to be a subject of study and discussion.

Aquinas’ work in epistemology, metaphysics, and natural theology has also been influential in Christian philosophy. He believed in the existence of a natural order that could be known through reason, and he argued for the existence of God through his famous “Five Ways”. These arguments have been widely discussed and debated in Christian philosophy, and they continue to be a subject of interest and study. Aquinas’ contributions to philosophical anthropology, ethics, and political philosophy have also been significant. He believed in the inherent dignity and value of human beings, and he argued for the importance of virtues and moral character in human life.

His work in these areas has been influential in Christian philosophy and theology, and it continues to be a subject of study and discussion today. Lastly, Saint Thomas Aquinas’ ideas have had a profound influence on the development of Christian philosophy, particularly in the areas of faith and reason, philosophy of language, epistemology, metaphysics, natural theology, philosophical anthropology, ethics, and political philosophy. His work continues to be studied and debated in Christian philosophy and theology, and his contributions to the field remain significant and influential.

Saint Catherine of Siena

Saint Catherine of Siena, born in Italy in 1347, was a prominent figure in the Catholic Church during the 14th century. She is best known for her mystical experiences, her role in the Avignon papacy, and her influence on the political and religious spheres of her time. As a Dominican tertiary, Catherine dedicated her life to prayer, fasting, and serving the poor. She was believed to have received numerous visions and messages from God, which she documented in her writings.

In the historical context of Saint Catherine of Siena, it is essential to understand the state of the Catholic Church during the 14th century. This was a period marked by the Avignon papacy, where the popes resided in Avignon, France, rather than Rome. This led to a significant decline in the church’s authority and integrity, as many questioned the legitimacy of the papacy. Catherine played a crucial role in urging Pope Gregory XI to return the papacy to Rome, which he eventually did in 1377.

Saint Catherine’s influence extended beyond the religious realm and into the political arena as well. She was actively involved in mediating conflicts within the Italian city-states and played a key role in negotiating peace treaties. Catherine’s diplomatic skills and unwavering faith earned her respect and admiration from both political leaders and the common people. Her ability to navigate complex and volatile environments solidified her reputation as a peacemaker and a voice of reason during tumultuous times.

Despite her immense contributions, Saint Catherine of Siena faced criticism and opposition from various quarters. Some within the church questioned the authenticity of her visions and messages, while others accused her of meddling in political affairs beyond her domain. However, Catherine remained steadfast in her beliefs and continued to advocate for justice, mercy, and reconciliation.

In the field of theology and spirituality, Saint Catherine’s writings have had a lasting impact on generations of followers. Her most famous work, “The Dialogue,” is a profound exploration of the soul’s journey to God and a testament to her deep mystical experiences. Catherine’s teachings on prayer, virtue, and love have inspired countless individuals to deepen their spiritual lives and seek union with the divine.

One of the key figures who has contributed to the study of Saint Catherine of Siena is Raymond of Capua, her spiritual director and confessor. Raymond played a crucial role in documenting Catherine’s life and writings, ensuring that her legacy would endure long after her death. His firsthand accounts of Catherine’s mystical experiences provide valuable insights into her spiritual journey and the challenges she faced.

Another influential individual in Saint Catherine of Siena is Pope Gregory XI, whom Catherine persuaded to return the papacy to Rome. Gregory’s decision to heed Catherine’s advice had far-reaching implications for the Catholic Church, restoring its credibility and authority. His collaboration with Catherine in bringing about this significant change in the church’s leadership underscores the profound impact she had on key figures of her time.

Saint Catherine of Siena was a remarkable figure whose legacy continues to inspire and challenge us today. Her unwavering faith, commitment to justice, and profound spiritual insights have left an indelible mark on the Catholic Church and the world at large. As we reflect on her life and teachings, we are reminded of the enduring power of faith, love, and compassion in shaping the course of history. Saint Catherine’s example serves as a beacon of hope and inspiration for all who strive to make a difference in the world and seek to live lives of meaning and purpose.

Abstract

This lecture is an attempt to trace the evolution of the concept of wisdom as found in the thought of Aristotle and Aquinas. This is done in terms of how the Greek concept of wisdom as an intellectual virtue is understood and used to express the Christian concept of wisdom as a gift of the Holy Spirit. The main aim is to understand how Aquinas derived the concept of wisdom from Aristotle’s philosophy and developed it in his theology.

This lecture is an attempt to trace the evolution of the concept of wisdom as found in the thought of Aristotle and Aquinas. This is done in terms of how the Greek concept of wisdom as an intellectual virtue is understood and used to express the Christian concept of wisdom as a gift of the Holy Spirit. The main aim is to understand how Aquinas derived the concept of wisdom from Aristotle’s philosophy and developed it in his theology.

The study is based on Book 6 of Aristotle Nichomachean Ethics and Question 45 of the second part of the second part of Aquinas Summa Theologiae. It concludes with a reflection on the relationship between wisdom and happiness.

Edmond Eh Kim Chew, OP

The Human-Animal Boundary

University of Macau

27-28 Nov 2015

The boundary between humans and non-human animals has been an integral part of philosophical discourse since antiquity. Attempts to draw a boundary between human and nonhuman life has involved the literary imagination as well as philosophical reflection. Throughout the centuries philosophers and poets alike have defended an essential difference – rather than a porous transition – between what counts as human and what as animal. The attempts to assign essential properties to humans (e.g. a capacity for language use, reason and morality) often reflected ulterior aims to defend a privileged position for humans with regard to animals (which were, in turn, interpreted as speechless, irrational and amoral). While this form of humanism has come under attack through animal rights initiatives in recent decades, alternative ways of engaging the human-animal relationship from a philosophical and poetic perspective are rare. The conference thus aims to shift the traditional anthropocentric focus of philosophy and literature by combining the question “what is human?” with the question “what is animal?” to explore productive ways of thinking with and beyond the human-animal boundary.

The boundary between humans and non-human animals has been an integral part of philosophical discourse since antiquity. Attempts to draw a boundary between human and nonhuman life has involved the literary imagination as well as philosophical reflection. Throughout the centuries philosophers and poets alike have defended an essential difference – rather than a porous transition – between what counts as human and what as animal. The attempts to assign essential properties to humans (e.g. a capacity for language use, reason and morality) often reflected ulterior aims to defend a privileged position for humans with regard to animals (which were, in turn, interpreted as speechless, irrational and amoral). While this form of humanism has come under attack through animal rights initiatives in recent decades, alternative ways of engaging the human-animal relationship from a philosophical and poetic perspective are rare. The conference thus aims to shift the traditional anthropocentric focus of philosophy and literature by combining the question “what is human?” with the question “what is animal?” to explore productive ways of thinking with and beyond the human-animal boundary.

Edmond Eh, O.P.

Symposium on Chinese Philosophy 2016,

Singapore-Hong Kong-Macau

29-30 April 2016

The Singapore-Hong Kong-Macau Symposium on Chinese Philosophy took place on 29-30 April 2016. It aims to foster dialogue and interaction among scholars and advanced graduate students primarily based in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau. Topics include any aspect of Chinese Philosophy, as well as papers dealing with comparative issues that engage Chinese perspectives. While preference is given to those from the region, participants from any geographic areas are welcome. Organised and sponsored by the Department of Philosophy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The Singapore-Hong Kong-Macau Symposium on Chinese Philosophy took place on 29-30 April 2016. It aims to foster dialogue and interaction among scholars and advanced graduate students primarily based in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau. Topics include any aspect of Chinese Philosophy, as well as papers dealing with comparative issues that engage Chinese perspectives. While preference is given to those from the region, participants from any geographic areas are welcome. Organised and sponsored by the Department of Philosophy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Edmond Eh, O.P.

Marian Devotion in relation to Lumen Gentium and Marialis Cultus

The lecturer, fr. Roland Mactal, introduced the Vatican II convoked in 1962 by Pope John XXIII, and closed by Pope Paul VI in the year 1965. Concerning Marian Devotion or Theology of Mary, he explains the two major themes “Aggiornamento†and “Ressourcementâ€. Aggiornamento means renewal or updating and Ressourcement means going back to the sources, here the sources will be the Scriptures.

Theology of Mary or Marian Devotion is mainly discussed in Vatican II Document Lumen Gentium, chapter eight. The lecturer explains the Parameters of Marian Theology. He introduces four parameters on the theology of Mary. Firstly, Mary as Theological Person which indicates Mary’s life and work as a mission expressed in Lumen Gentium, numbers 54 to 59.

Secondly, Mary as the Spiritual Subject, in which Mary is considered as one of us who experiences what we experience. In other words, that is the Process of Individuation. This concept is expressed in Lumen Gentium, numbers 66 to 67.

The third parameter is Concrete Universal in which Mary is presented as Model, Archetype or Exemplar of the Church. This typology reveals the relation between Mary and the Church. This parameter is taken from Lumen Gentium, numbers 60 to 65.

The last parameter presents Mary as Historical Subject. This parameter concerns the Anthropological and cultural identity of Mary, regarding the questions of who Mary is and where she is from. This parameter leads us to understand that Mary is an anawim, which means she is a poor of YHWH. This parameter can be found in Lumen Gentium, numbers 52 to 53.

Another concept that the Lecturer discussed was Mary as Mediatrix. The Mediatrix is attributed to Mary only as a title. However, many people have been proposing it to become a dogma. He continues to explain that there are some opposite ideas on this issue. Some propose that Jesus Christ is the Only Mediator, quoting the Letter of St. Paul to Timothy 2:5-6.

The counterpart explanation of this is that the mediation of Jesus is unique and ontological and cannot be replaced. The mediation of Mary is intercessory and dynamic. Mary’s mediation is through intercession, because she participates in the life of Jesus Christ. It does not obscure or diminishes the unique mediation of Christ, rather shows His power. (L.G. # 60) Because of the superabundance of merits she received from Christ, she is the Mediatrix. Lumen Gentium, number 62 entitles Mary as “Advocate, Auxiliatrix, Benefactressâ€.

Concerning the Apostolic Exhortation Marialis Cultus of Pope Paul VI, the lecturer explains the role of Marian devotion in relation to the Liturgy. The Liturgy is the official public prayer of the Church. The Vatican II emphasizes to restore and enhance the Liturgy by active and fruitful participation of the faithful in it.

Marialis Cultus expresses in terms of renewal of private Marian devotion, such as the Rosary in relation to the Liturgy of the Eucharist and to the Liturgy of the Hours. Furthermore, in Marialis Cultus Marian teachings were the union of Mary with the mystery of Christ and the Church and the placement of Marian devotion in its right perspective.

Concerning Marian Devotion, Catholic veneration of the Mother of God has two aspects: Public (official) and Private (pious devotions and exercises). The Public Official Liturgical Prayers are the Holy Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours. Mary, the Mother of God, is commemorated in the daily celebration of the Eucharist. The Church has officially approved four solemnities, three feasts and nine memorials in honor of Mary within the Liturgical Year. Mary is featured in the liturgy in various ways such as Hymns, prayers and the readings.

As explained in Marialis Cultus, the Angelus and the Holy Rosary are the two exercises of piety, which are both biblically based. The substantial part of these devotions is primarily taken from the Gospel. The Angelus reminds us of the Paschal Mystery of Christ. The Holy Rosary which focusses on the salvific events of the life of Christ is called the Gospel prayer.

In Marialis Cultus, Pope Paul VI recognizes the Dominicans’ tradition on Holy Rosary as he mentions: “among these people special mention should be made of the sons of St. Dominic, by tradition the guardians and promoters of this very salutary practice, the praying of the Holy Rosary.†(43)

The lecturer concludes that “Marialis Cultus proposed Mary as model of the Church in divine worship, because she represents the Church at worship at its deepest level.â€

Francis Nge Nge, OP

FAUSTO GOMEZ OP

faustogomez@yahoo.com

Remember John, the patient with metastatic brain cancer? After discarding the option of euthanasia, which shortens life unethically, and of dysthanasia, which postpones death unduly, John has accepted orthothanasia or allowing to die, and signed a “living will.†He has also asked his elder brother physician to please continue taking care of his terrible pain, and to his daughter, not to leave him alone.

Once in a medico-moral conference in Manila, I heard a psychiatrist say: “Ask not why a patient requests for euthanasia, but why life loses its meaning.â€Â Indeed, finding meaning to the end of life, and to suffering can make of euthanasia not an option.

MEANING OF SUFFERING AND PAIN

The word “suffering” is derived from the Latin word “sufferre” or” sub-ferre,” meaning to bear: the sufferer is a bearer of burdens. Although mainly physical in nature, pain is closely related to suffering, which is more than just bodily pain. As Eric Cassell says, pain is undergone by the body, while suffering by the person. Radically, however, the experience of pain and suffering belongs to the whole person, who is body-soul. Often, the terms pain and suffering are used interchangeably. Suffering may be physical and moral (cf. John Paul II, Salvifici Doloris).

May suffering and pain be useful? Do they have a positive meaning? In the order of nature, pain and suffering especially severe and chronic are evils that attack our integrity as human beings, limit our freedom and independence, develop in many of us feelings of anger, rejection and guilt – and the fear of alienation.

As an evil, suffering has to be avoided and fought. As an inevitable part of our earthly life – sooner or later, an intruder into our life –, we are asked to face it humanely, that is, reasonably, responsibly, and – as much as possible – courageously. In the order of divine grace, suffering is an evil, but it can become – when lovingly and patiently borne – an instrument of purification and salvation.

Suffering, including physical pain, is truly mysterious: mysterium doloris. Suffering is part of the project of human life that is realized in love. God is not indifferent to our infirmities. In fact, in his Son Jesus Christ, he shared our sufferings, and is with us when we are in pain.  Out of love Christ died for all humanity. We, Jesus’ disciples, join our sufferings to the sufferings of Christ.  The deepest meaning of the mystery of suffering is co-redemptive suffering or suffering as an act of redeeming love (Col. 1:24). How do we bear our cross – our darkness? We try to bear it with courage, patience and hope – and prayer. How do we help others carry their cross, their pains and sufferings? By relieving their suffering and accompanying them with compassion and prayer.

COMPASSION WITH THE DYING

True compassion with the dying – with our brother John – is not the false compassion of euthanasia that kills, but the true compassion of charity as love of neighbor, of all neighbors, especially the poor and the sick neighbor – as Jesus witnessed and taught us.

Following Christ, the Good Samaritan – the best paradigm of the healing and caring ministry –, we all have to be at the side of those who suffer in our families and communities, and to help them bear their sufferings. We have to accompany, in particular, the terminally and incurable ill. In his play Caligula, Albert Camus put these words in the mouth of Scipio: “Caligula often told me that the only mistake one makes in life is causing suffering to others.†We have to be at the side of the terminally ill in a nonjudgmental, non-paternalistic, but understanding, respectful and prayerful attitude.

The terminally ill patients need not only pain relief, but also empathetic solidarity; need not philosophical or theological explanations but compassion. In general, health care professionals try to free patients from pain, while significant others – immediate family, friends, the pastoral team and also the healthcare team – provide support and protection, security – and “a warm heart.â€

Another important point to underline: those serving the terminally ill, in particular believers in Jesus, realize that the sick evangelize them, too, by silently inviting them to reflect on the gifts of health and relationships, on God, on our own sufferings, on the finitude of life, and on their loving union with the Crucified and Risen Lord.

How do we help others to die? We help them to die peacefully by praying with them and their families, by being with them, by accompanying them. While we ask the Lord to help us face our own death with courage, we ask him to help us face the death of our loved ones and our neighbors with compassion, with sympathetic solidarity. The Lord is particularly present in those who suffer. When we visit patients like John, we believe that Jesus is present in them. Jesus keeps telling us: “I was sick and you visited me†(Mt 25:36).

THE REALITY OF DEATH

Death is inescapable, inevitable, and utterly undeniable: “Man’s days are like those of the grass, like a flower of the fields it blooms; the wind sweeps over him and he is gone, and his place knows him no more (Ps 103:15-16).

Pain and suffering are travelling companions on our journey of life. They appear as veiled or clear warnings of the reality of death. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church puts it, Illness “can make us glimpse death†(CCC, 1500).

As Christians, we are asked not only to accept our death but also to help others accept theirs. Physicians, and other healthcare givers, are asked by their profession – and by their faith – to help the terminally ill and dying accept their death at the proper time. To be able to do this responsibly, they must have accepted the reality of death not as a failure of medicine (except when there is a gross negligence), but as a natural end of earthly human life.

For Christians, death is also a very important and difficult reality, but not the ultimate reality. The ultimate reality is eternal life with God: “Where might the human being seek the answer to dramatic questions such as pain, the suffering of the innocent and death, if not in the light streaming from the mystery of Christ’s Passion, Death and Resurrection?†(John Paul II). “I am not dying. I am entering life†(Saint Therese of the Child Jesus). “If you are an apostle, you will not die. You will change of house and nothing more†(St. JosemarÃa Escrivá).

Objective ethical guidelines and answers are not hard, but personal decisions at the end of life are often extremely difficult. The bishops of Illinois advice: “We must not let some of the ambiguities of end-of-life decision making lead us, on one hand to a neurotic fear that we will incur Christ’s judgment for not acting with sufficient care and, on the other hand, to choose reckless or misguided care for our loved ones. In consulting with legitimate Church teaching, our conscience can be formed so that decisions made even in emotionally laden situations are moral, compassionate and appropriate.â€

On earth we are pilgrims, co-travelers on the way to the Father’s house: we are citizens of heaven. Our life is God’s gift which we must treasure from womb to tomb. Our faith, God’s unmerited gift, is hopeful. Our love – God’s love – makes of our life a faithful and hopeful journey to heaven. Certainly, love is stronger than death.

At the end of his earthly life, John is suffering with continuing pains. He has signed his “living will.†His brother physician is helping him diminish his pains by prescribing the appropriate painkillers. His daughter, family and friends are giving him “a warm heart†so that he does not suffer from loneliness, from feeling alone, which would mean social death. They all, with the members of his parish are praying with and for him. John has asked for the Anointing of the Sick and Holy Communion. He is calm and at peace within and without. He is ready to go.

“You, dear Lord, have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you†(St. Augustine). May God bless us all!

(Published by O Clarim, June 23, p. 10)

Â

The boundary between humans and non-human animals has been an integral part of philosophical discourse since antiquity. Attempts to draw a boundary between human and nonhuman life has involved the literary imagination as well as philosophical reflection. Throughout the centuries philosophers and poets alike have defended an essential difference – rather than a porous transition – between what counts as human and what as animal. The attempts to assign essential properties to humans (e.g. a capacity for language use, reason and morality) often reflected ulterior aims to defend a privileged position for humans with regard to animals (which were, in turn, interpreted as speechless, irrational and amoral). While this form of humanism has come under attack through animal rights initiatives in recent decades, alternative ways of engaging the human-animal relationship from a philosophical and poetic perspective are rare. The conference thus aims to shift the traditional anthropocentric focus of philosophy and literature by combining the question “what is human?” with the question “what is animal?” to explore productive ways of thinking with and beyond the human-animal boundary.

The boundary between humans and non-human animals has been an integral part of philosophical discourse since antiquity. Attempts to draw a boundary between human and nonhuman life has involved the literary imagination as well as philosophical reflection. Throughout the centuries philosophers and poets alike have defended an essential difference – rather than a porous transition – between what counts as human and what as animal. The attempts to assign essential properties to humans (e.g. a capacity for language use, reason and morality) often reflected ulterior aims to defend a privileged position for humans with regard to animals (which were, in turn, interpreted as speechless, irrational and amoral). While this form of humanism has come under attack through animal rights initiatives in recent decades, alternative ways of engaging the human-animal relationship from a philosophical and poetic perspective are rare. The conference thus aims to shift the traditional anthropocentric focus of philosophy and literature by combining the question “what is human?” with the question “what is animal?” to explore productive ways of thinking with and beyond the human-animal boundary. The Singapore-Hong Kong-Macau Symposium on Chinese Philosophy took place on 29-30 April 2016. It aims to foster dialogue and interaction among scholars and advanced graduate students primarily based in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau. Topics include any aspect of Chinese Philosophy, as well as papers dealing with comparative issues that engage Chinese perspectives. While preference is given to those from the region, participants from any geographic areas are welcome. Organised and sponsored by the Department of Philosophy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The Singapore-Hong Kong-Macau Symposium on Chinese Philosophy took place on 29-30 April 2016. It aims to foster dialogue and interaction among scholars and advanced graduate students primarily based in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau. Topics include any aspect of Chinese Philosophy, as well as papers dealing with comparative issues that engage Chinese perspectives. While preference is given to those from the region, participants from any geographic areas are welcome. Organised and sponsored by the Department of Philosophy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.