We give Thanks to God for His abundant Love upon us!

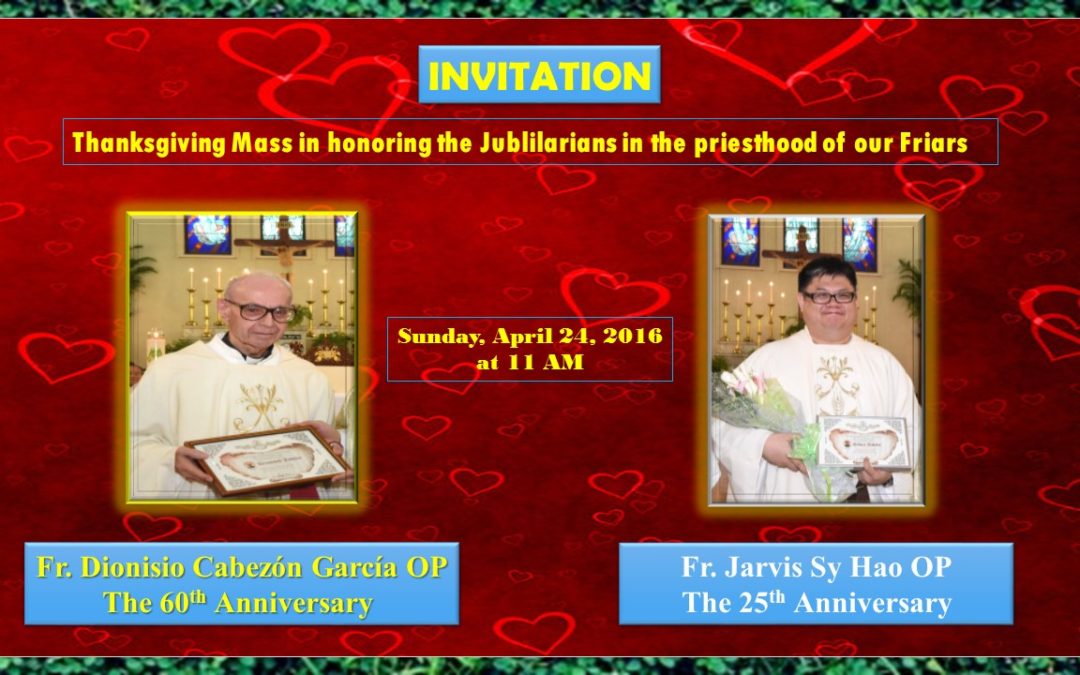

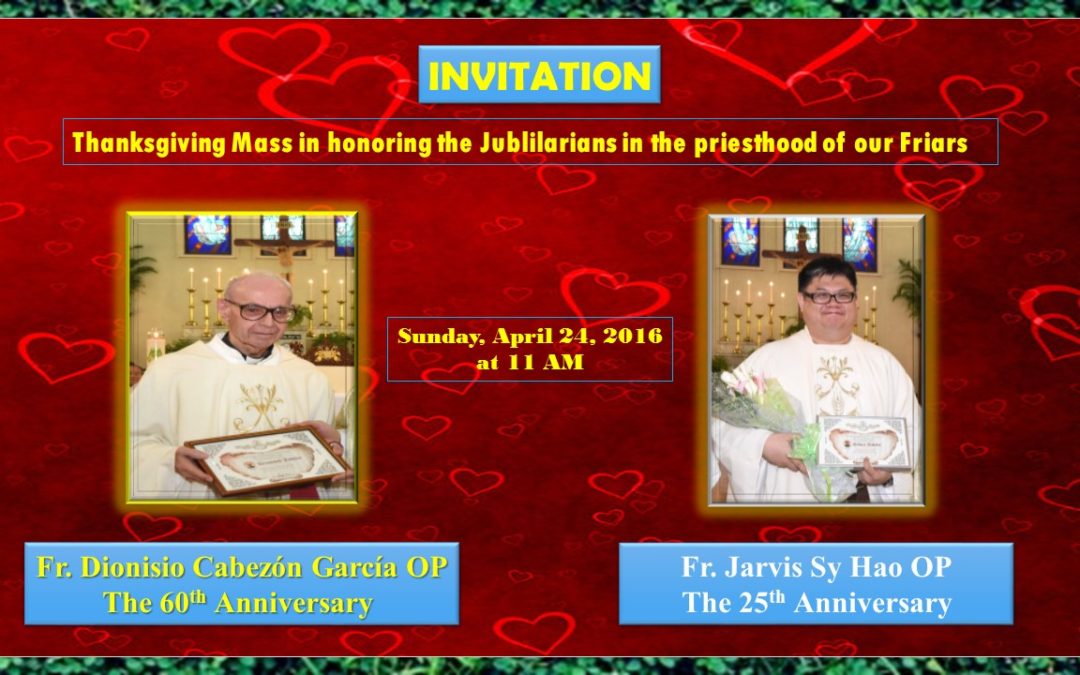

On the coming Sunday, April 24th, 2016 at 11 AM, the Friars of Saint Dominic Convent in Macau joyfully celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Fr. Dionisio Cabezón GarcÃa OP and Silver Jubilee of Fr. Jarvis Sy Hao OP in their ordination to the priesthood. We cordially invite you to join us this very special event of Thanksgiving Mass in honor our beloved Friars for their so many years of serving God.

The Brothers of Saint Dominic Convent.

FAUSTO GOMEZ OP.

The Holy Year of Mercy invites Christians to be merciful. Mercy, or compassion for the needy, is a necessary expression of love of neighbor, which includes comforting the suffering. In the heart of the Sermon on the Mount Jesus gives the Second Beatitude: “Blessed are those who mourn for they shall be comforted†(Mt 5:4), which means to be sorry for the suffering and miseries in the world and for our miseries and sins. Comforting those who suffer is a spiritual work of mercy.

Our humanity is a wounded humanity. So much suffering in our world: the lonely elderly, the battered wife, the abandoned child, the family of refugees, the persecuted, tortured and killed, the youth surviving a meaningless life, the “different†among us who are alienated, new slaves … Â

How may God be a tender mother and allow so much misery and poverty and violence and injustice? Suffering is truly mysterious, mysterium doloris! How do we relate suffering to an all-good and omnipotent God? And the perennial question: Why do innocent children suffer? Other heart-breaking questions are these: Why the terrorist massacres? “Why the Holocaust?†Why, Lord, did you remain silent? How could you tolerate all this?†(Benedict XVI, Address at Auschwitz-Birkenau: May 28, 2006).

Certainly the God of our Lord Jesus Christ is not a vengeful, nor a masochistic God, but the compassionate Father of the prodigal son, the Abba of his Son Jesus Christ, who died on the Cross! We believe that God is love (I Jn 4:16), and that there is heaven. Suffering is part of the project of human life, which is realized in love. God does not rejoice in our infirmities; in fact, in his Son Jesus Christ, he shared suffering with us. Our God is not an insensitive God. Jesus, God and man, wept over Jerusalem, the beautiful city that some years later would be totally destroyed (Lk 19:41-48). Jesus weeps seeing the terrible sufferings of so many people in the world! The only answer to those questions is Christ on the cross. Out of love, Christ died for all humanity. But He did not do away with suffering and death: “He came down from heaven to take them upon himself; he did not do away with them, he did something more: he gave them meaning and lit them up from within, transfiguring them and making them God-like” (Charles Journet). (Where was God on September 11, 2001, on March 11, 2004, On December 26, 2004, on November 13, 2015…? He was nailed to the Cross! He is on the cross with those who suffer).

Suffering may become a path to meet God. With God’s grace and our cooperation, the cross may be turned from a place of pain and suffering into “an appointment with the Crucified Lord” (J.M. Cabodevilla). The saints not only bore their sufferings patiently but also joyfully – for the love of God. They even asked the Lord to increase their sufferings so that they would be united, in a closer manner, to the Crucified Lord, and thus become co-redeemers with Him. The deepest meaning of the mystery of suffering is co-redemptive suffering (Col 1:24).

The mystery of evil continues! And in the midst of suffering, the mystery of an omnipotent and merciful God! We know that God loves us, “God so loved the world that He gave his only begotten Son.†Moreover, we believe Jesus died on the cross to show us the evilness of sin: Sin is darkness, night, and unhappiness: a betrayal of God’s love and of the blood of Christ shed for us. Facing those sufferings, we are asked by our humanity and our faith to help others carry their cross not with sermons, but with compassion. One of the gravest things one can do in life is to make others suffer (A. Camus). Hereafter, I reflect on the suffering of our loved ones and of our own suffering.

Pope Francis has often used the image of a field hospital after a battle and applied to a merciful Church. She is the tender mother who cares for the wounded. She cares in particular for her children who are sick, or abandoned in many places.

As Christians, we have to love the neighbor. Who is my neighbor? In the lovely Parable of the Samaritan, Jesus asked the teacher of the law: Who among the three in the parable is your neighbor? The teacher answered: “The one who showed mercy†(Cf. Lk 10:25-37). Blessed Paul VI said at closing of Vatican II that the model of the spirituality of the Council was the story of the Good Samaritan.

How do we face the suffering of others? To face properly the pain and suffering of others, we need to face properly pain and suffering in our own life. If we are not able to integrate our own sufferings in the story of our personal life, we will have a hard time in helping others bear their sufferings in a humane and/or Christian way.

How do we face our own personal suffering? The Psalmist says: “It is good for me that I have been afflicted†(Ps 119:71).We try to face our sufferings and pains with courage, hope and respect for life – and prayer. With courage: we try hard to be patient and to persevere in patience: fortitude is the cardinal virtue that helps us with patience and perseverance to carry the cross of life – our pains and sufferings. We struggle to carry our cross with hope: God cares for us, is in us and in front of us as our hope. We bear our sufferings respecting our life, which belongs to God, up to its end – against the shortcuts of euthanasia and also against the undue prolongation of dying through useless and extremely burdensome treatments. As we fix our eyes on Jesus on the Cross, we also think of our own cross: you know that you will be saved on your cross, and I know that I will be saved on mine! “If anyone wants to be my disciple let him deny himself, take up his cross and follow me.†Jesus, our savior and friend, adds: “My yoke is light,†“come to me all who are burdened and I will give you rest.†No wonder, for the saints, the truly happy ones, when the cross comes, it is the Lord who comes!

How do we face the suffering of others? We face the sufferings of others with compassion and in solidarity with them – and with prayer. The suffering persons need not only pain relief, but also empathetic solidarity. In general, healthcare givers try to free the patient from pain, while the significant others – immediate family, friends, and also the members of the healthcare team, especially physicians and nurses – provide support, protection, security, and “a warm heart” so that patients may be able to suffer human weakness in solidarity: homo patiens and homo compatiens. Philosopher E. Levinas reminds us that our answer to the suffering of the other is compassion, not explanation. True compassion, however, is not expressed by cooperating in euthanasia unjustly called mercy killing! How may killing be merciful? Compassion implies solidarity, or justice plus love of neighbor, a love that respects the dignity and rights of the human person, including the fundamental right to life. God is the Lord of life and death. We are only stewards.

Following Christ, the Good Samaritan – the best paradigm of the healing and caring ministry -, we all have to be at the side of those who suffer in our families and communities, to help them bear their suffering, and not to increase it! In his play Caligula, Albert Camus put these words in the mouth of Scipio: “Caligula often told me that the only mistake one makes in life is causing suffering to others.” We have to be at the side of those who suffer in a nonjudgmental, not paternalistic, but understanding, respectful, merciful and prayerful attitude, as they pass through different psychological stages, like the classical five of Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

Another point we must not forget: The sick around us evangelize the healthy. The suffering of others, particularly of our loved ones, calls us to reflecting on the meaning of life and of suffering. The sick invite us silently to meditate on the gifts of our health and relationships, on God, on our own sufferings, on the finitude of our life and on our constant need to be united to the passion, death and resurrection of Christ.

Is there a pedagogy of suffering? When suffering knocks on our door, what ought we to do? I wish to share with you my own recipe for personal suffering and of the loved ones.

We do not blame God. God permits but does not like our suffering. In Christ, He assumed our suffering, and He accompanies us.

We ask God to help us either by eliminating our suffering or pain, or by aiding us to bear it. We believe in God the Father who loves each one of us  and we pray – like Jesus – for help: “My Father, if this (passion, crucifixion) cannot pass me by without my drinking it, your will be done†(Mt 26:42).

United to the Crucified Lord, we try to carry our cross patiently; perhaps limping at times, perhaps complaining a bit! “God does not give more suffering than what can be endured, and, in the first place, He gives patience†(St. Teresa of Avila)

We try to carry our cross, our suffering joyful in hope (Rom 12:12). “Blessed are the sorrowful, they shall be consoled†(Mt 5:4).

We bear our sufferings out of love: “The way we came to understand love was that he laid down his life for us; we too must lay down our lives for our brothers†(I Jn 3:16).

And from beginning to end, we pray. We ask the good Lord to remedy our weakness, our impatience, our irritation, our depression, our hopelessness …

If we follow this recipe, we shall love the cross: not for its own sake but because of the Crucified Lord. Then, our suffering – joined to Christ’s – becomes redemptive suffering: “It makes me happy to suffer for you, as I am suffering now, and in my own body to do what I can to make up all that has still to be undergone by Christ for the sake of his body, the Church†(Col 1:24

Pope Francis speaks of the Church mainly as mother, as a tender mother, and – he adds – and so must also be the followers of Christ, the Merciful One, who is “the face of the Father’s mercy†(Pope Francis, Misericordiae Vultus, 1).

Â

FAUSTO GOMEZ OP

Every Easter I am joyfully surprised by the attitude of Jesus’ disciples after the Pentecost experience. The first Christians are a happy people. Two qualities adorn their lives: the joy of their faith in the Crucified and Risen Lord and the courage to suffer persecution for his sake. When I was a young student I could not understand why some of my teachers appeared to be sad.

Joy is a passion and an emotion of the human person. It stands for true satisfaction and delight, for the gladness produced by goodness, beauty, God. Pope Francis underlines this joy in his Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, or The Joy of the Gospel (2013). How can Christians not be joyful? We believe that God is our Father, Jesus is our savior and brother, and the Holy Spirit, our advocate and consoler. Christian joy is a shared joy: We are all brothers and sisters. Fraternal/sisterly love increases our personal joy: “When many rejoice together, the joy of each is richer; they warm themselves at each other’s flame†(St. Augustine).

Believers with others rejoice contemplating God’s creation: “The hillsides are wrapped in joy, the meadows are covered with flocks, the valleys clothed with wheat; they shout and sing for joy†(Ps 65: 12-13). Joy is one of the fruits and blessings of the Holy Spirit (Gal 5:22).

If we go through the main events of the life of Jesus we feel the presence of joy in his life and message. Contemplate the Annunciation to Mary: “The angel came to her and said: ‘Rejoice, full of grace, the Lord is with you’†(Lk 1:28). The Visitation of Mary: How is it, Elizabeth says, “that the mother of the Lord comes to me? The moment your greeting sounded in my ears, the baby within me suddenly moved for joy†(Lk 1:44). The angel announcing to the shepherds the Birth of Jesus: “Don’t be afraid; I am here to give you good news, great joy for all the people. Today a Savior has been born to you†(Lk 2:10-11 and 20).We perceive the joy of Zacchaeus welcoming Jesus to his house (Lk 19:6). The lovely parables of the lost show the joy of the Father in heaven over the found sheep, silver pieces and prodigal son: “Let us rejoice and celebrate for my younger son has come back home†(see Lk 15:6, 9, 32.

The core of Jesus’ preaching is The Beatitudes, which are eight forms of happiness: Happy are the poor in spirit, the merciful, and the peacemakers – and even those who mourn! The path presented to us by Jesus is the path of joy and happiness, and not the path of wealth, of pleasure and power but the path of spiritual poverty. Therefore, Jesus tells us, “Be glad and rejoice!â€(Mt 5:12). In truth, the Beatitudes say to us: “O the bliss of being a Christian, the joy of following Christ†(W. Barclay).

Jesus calls sinners to conversion, which causes joy – joy in the sinner, in the community and in heaven: “I tell you, there will be more rejoicing in heaven over one repentant sinner than over ninety-nine upright people who have no need of repentance†(Lk 15:10).

Jesus is conversing with his apostles during the Last Supper. He is going to be crucified and die the next day Good Friday.  He tells them that God loves them, that they are the branches attached to the vine, that is, to him. Jesus adds: “I have told you this so that my own joy may be in you and your joy be complete†(Jun 15: 11). A little later in the evening, and after announcing to them his departure, He tells them: “You are sad now, but I shall see you again, and your hearts will be full of joy and that joy no one can take away from you†(Jn 16:22).

There is great joy in the presence of the Risen Lord: “They were still incredulous for sheer joy and wonder†(Lk 24:41). There is wonderful joy in the disciples after witnessing the Ascension of Christ: “As he blessed, he left them, and was taken up to heaven, they fell down to do him reverence, then returned to Jerusalem filled with joy†(Lk 24:52).

After the Resurrection of Christ, the apostles preached the Gospel with great courage and joy. They were often persecuted, imprisoned, flogged for doing so. They were “glad for having had the honor of suffering humiliation for the sake of the name†(Ac 5:41). What name? Jesus our Lord! Indeed, the Resurrection of the Lord is joy! The converts of Paul and Barnabas “were filled with joy and the Holy Spirit†(Ac 13:51). The jailer of Paul and Silas in Philippi rejoiced with his whole household at having received the gift of faith in God (cf. Ac 16:34). After baptizing the Ethiopian eunuch, Philip was snatched away by the Spirit and disappeared, “but the eunuch continued on his way rejoicing†(Ac 8:39).

How did the first Christian communities experience Christ’s Resurrection?  By being faithful, joyful and passionately in love with the Crucified and Risen Lord: “They remained faithful to the teaching of the apostles, to fraternity, to the breaking of the bread, and to prayer… They shared their food gladly and generously; they praised God and were looked up to by everyoneâ€! (Ac, 2:42, 46-47).

Pascal says: “No one is as happy as an authentic Christian†or, we may add, as an authentic believer or an authentic human being! Are there many authentic Christians? Mary Our Lady rejoices: “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord, my spirit rejoices in God my Savior†(Lk 1: 46-47). The saints are true Christians and that is why they are all joyful: “The saints rejoiced all their lives long, like men at a feast†(St. Athanasius).

The disciples to Emmaus are sad. They have a reason to be sad: they believe Jesus is dead. What is bad is that those who believe that Jesus rose from the dead are sad (J. L. Martin Descalzo). Christians who are sad, Bonhoeffer says, have not understood the Resurrection, the joy of the resurrection! “It is impossible to be sad in the presence of the Risen Lord†(Schillebeeckx). No wonder, the monk and theologian Evagrius Ponticus (4th century) added, to the traditional seven capital sins, the eighth capital sin: sadness.

What is the main cause of Christian joy? True love is the source of real happiness and joy. Love is joyful. Indeed charity as love of God and of all neighbors causes real joy: Love is, with peace and mercy, an internal act of charity.  You and I ask: Why should we rejoice always? Life is full of sufferings and pains and violence and injustice! Why should we? Because in spite of our miseries God loves us, and Jesus heals us, and the Holy Spirit consoles and strengthens us! Disciples of Jesus through the centuries even when persecuted and martyred were and are “full of joy†(Ac 5:41).

Life, our life on earth is also visited by suffering. Suffering, however, is not opposed to happiness: “It makes me happy to suffer for you†(Col1:24). There is a time to mourn: “Blessed are those who mourn; they shall be comforted†(Mt 5:4). When we are hurting, Jesus our Savior, brother and friend invites us to come to him: “Come to me all you who are weary and find life burdensome, and I will refresh you†(Mt 11:28). Suffering is part of our life, yes, but suffering is not the word that gives meaning to our life: love is. And love, only love can make suffering light, joyful and hopeful. One of my favorite priest writers is José Luis Martin Descalzo who passed away at sixty after years in dialysis. He wrote: “I confess that I never ask God that he cures my sickness. This would seem to me an abuse of trust. I ask him, yes, that He helps me bear my suffering with joy.†To the Ten Commandments, Descalzo adds the eleventh: “Be joyful.†The poet and mystic Rabindranath Tagore writes: I was sleeping and dreamed that life was joyful; I woke up and saw that life was service; I began to serve and saw that serving was joy.

The virtue of loving hope is permeated by joy: “Be joyful in hope†(Rom 12:12). Hope is the virtue of the pilgrim. We are pilgrims on the way to our Father’s house. We cannot be perfectly joyful here on earth, but we are certainly joyful already because God’s love is in our hearts. Love is hopeful: we believe in heaven, in eternal life as the object of our hope and the end of our longing (cf. 1 Jn 2:25). We strongly believe that we shall be outrageously happy in the life to come – after a happy ending! On the way, we truly rejoice because we believe, love and hope.

We Christians are Easter People and Alleluia is our song! On the journey of life, St. Augustine invites us to sing joyfully with him: “Let us sing now… in order to lighten our labors. Sing but continue your journey, making progress in virtue, faith and right living.†He adds: “Make sure that your life sings the same tune as your mouth.â€

We joyfully hope and pray that Jesus will tell us at the end of our earthly pilgrimage: “Come, share your master’s joy†(Mt 25:21-23).

(Published in O Clarim, The Macau Catholic Weekly, April 8, 2016)

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

FAUSTO GOMEZ OP

A few days ago, a young man asked me: “What is the real meaning of Easter?†After conversing with him for a while, I went home and wrote a few thoughts on Easter. Let me share these thoughts with you, dear reader.

The Resurrection of the Lord is the Good News: “If Christ had not risen, our faith would be in vain,†St. Paul tells us. But Christ is risen, and, therefore, our faith is the true foundation of life, our hope looks to heaven and our charity is the step forward in our pilgrimage to the house of the Father. Someone asked Joseph of Arimathea: “Why did you give your great tomb to someone else (to Jesus)?†“Oh,†said Arimathea, “He only wanted it for the weekend.â€Â Kidding aside, the Lord is risen, He was raised to a new and glorious life, and He lives!

Christians through centuries, particularly the first disciples of Jesus, have proclaimed in words and deeds: We are Easter People! For us Christians, the resurrection of Christ is the central mystery of our faith. Saint Paul writes: “In the first place I taught you what I had been taught myself, namely that Christ died for our sins, in accordance with the scriptures; that he was buried, and that he was raised to life on the third day, in accordance with the scriptures†(I Cor 15:3-4).

To be a Christian yesterday, today and always means to be able to say with God’s grace – like Mary Magdalene, like the apostles – I have seen the Lord! To see the Lord in life implies to experience his presence as Crucified and Risen Lord, to be transformed by him, to be seduced by his life and mission. How may we know that indeed we have seen the Lord Jesus?

How did the first Christian communities show that they had experienced Christ’s transforming presence? Their answer: “They remained faithful to the teaching of the apostles, to fraternity, to the breaking of the bread, and to prayer… They shared their food gladly and generously, praised God and were looked up to by everyone†(Acts, 2:42, 46-47).

Is the Lord our Risen Lord? If we have encountered Jesus in our life, then he is raised from the dead. Where may we encounter the Risen Lord? We may encounter the Risen Lord in the praying and fraternal community, in the Church, which is the Mystical Body of Christ and a Community of Disciples: “Where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in their midst†(Mt 18: 19-20). We recall that the apostle Thomas did not experience the presence of the Risen Lord when he was absent from the apostolic community.

We may encounter the Risen Lord in the Sacraments of the Church: in Baptism (the catechumens baptized on Easter Vigil experienced Jesus raised from the dead), in Penance, and above all in the Holy Eucharist: “This is my body,†Jesus said, “This is my blood†(Mt 26:28-28). Furthermore, we may experience the Risen Lord in the Word of God, the Sacred Scriptures, particularly when proclaimed in the Church. We remember the two disciples of Emmaus, who after recognizing the Lord in the breaking of the bread said to one another: “Were not our hearts burning inside us as he talked to us on the road and explained the Scriptures to us?†(Lk 24:32).

We may encounter Christ the Lord in our mission, in preaching and witnessing the Good News. This is the great resurrection command from the Risen Lord: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations… And know that I am with you always, until the end of the world†(Mt 28:19-20). We may also feel the presence of Jesus in our lives if we love the little ones, that is, the poor, the sick, and the abandoned on the roads of life. These words of Jesus resound in our hearts in a special way through Easter: “What you do to the least of my brothers, you do it to me†(Mt 25:40). As it has been often said: Jesus is personally present (“I was hungry and you gave me foodâ€) in the “poor†and in those who are close to the poor.

How may we experience Christ’s resurrection, Easter today? We may experience him by turning away from sin, which is darkness, and by practicing virtue, which is light. Easter is light: the light of Christ, Jesus the Easter Candle. True Easter, according to Saint Athanasius, is abstention from sin, practice of virtue and the passage from death to life. But, how may one know that he or she has passed from death to life? “We know for sure,†St. John tells us, “that we have passed over from death to light because we love our brothers†(I Jn 3:14).

One fact from the Easter narratives that moves me deeply is the courageous, hopeful and joyful love of the apostles and the first Christians. These proclaimed the Word, focused on the death and resurrection of Jesus, in an incredibly bold manner. They were outrageously joyful – even in suffering and particularly in martyrdom. At times in our life, it is hard to be joyful. But we know that, as witnesses of the resurrection of Christ, our life ought to be permeated essentially by joy.

Are we Easter People? Indeed, we are: We Christians firmly believe in the resurrection of Jesus the Lord. His Resurrection is the guarantee of our own resurrection: “Christ has been raised from the dead, as the first-fruits of all who have fallen asleep. As it was by one man that death came, so through one man has come the resurrection of the dead. Just as all die in Adam, so in Christ all will be brought to life†(I Cor 15:20-22).

Believers in Jesus are Easter People and strive hard to behave as witnesses of his resurrection – of his unconditional and universal love. Indeed, we are Easter People and Alleluia is our song. Alleluia, that is, praise the Lord!

May those around us notice that we are Easter People by the way we treat them with kindness and compassion. Dear co-pilgrim on the journey of life…, Happy Easter!

(Published by O Clarim: March 24, 2016)

FAUSTO GOMEZ OP.

The paths of mercy are many. The corporal and spiritual works of mercy are paths of mercy (cf. CCC 2447). Pope Francis in his Bull of Proclamation of the Jubilee of Mercy Misericordiae Vultus, the Face of Mercy (no. 15): “It is my burning desire that, during this Jubilee, the Christian people may reflect on the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. It will be a way to reawaken our conscience, too often grown dull in the face of poverty. And let us enter more deeply into the heart of the Gospel where the poor have a special experience of God’s mercy. Jesus introduces us to these works of mercy in his preaching so that we can know whether or not we are living as his disciples.â€

The three classical exercises of penance are paths of mercy: prayer, fasting and almsgiving. “Prayer with fasting and alms with uprightness are better than riches with iniquity… Almsgiving saves from death and purges every kind of sin†(Tob 12:8-9; Dan 4:27; cf. Mt 6:2-4, 5-6, 16-18; cf. EG 193). Often, prayer is presented as directed to fasting and almsgiving – to virtuous living.

Fasting to be a good act must be accompanied by almsgiving. Fasting without almsgiving is not a saving act on the way to heaven. It is insufficient as John Chrysostom, Ambrose and Augustine tell us. St. Peter Chrysologus (406-450) writes: “He who does not fast for the poor fools God.†On the other hand, fasting with almsgiving is pleasing to God. St. Clement of Rome (d. end of first Century) writes: “Almsgiving is as good as repentance from sin; fasting is better than prayer; almsgiving is better than either.â€

In the teaching of Sacred Scriptures, patristic and classical theology true almsgiving is a necessary expression of mercy and compassion. In his Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium Pope Francis writes: “The wisdom literature sees almsgiving as a concrete exercise of mercy towards those in need†(EG 193). For those who believe in God, almsgiving is an obligation (Tob 1:7-11; Sir 7:10). Why? Because, all need to practice charity as love of neighbor, as merciful love, which is the highest expression of love of neighbor. All the Fathers of the Church recommend strongly and persistently sharing of goods, almsgiving. St Cyprian, the first Father to give us a theological treatise on almsgiving entitled On Almsgiving, speaks of almsgiving as an obligation of all Christians. He says that almsgiving is an act of mercy, an act of justice, and a means of penance for our sins and for obtaining forgiveness for them.

Almsgiving is an outward or external act of mercy. Based on Sacred Scriptures, the Fathers of the Church consider almsgiving also an expression of justice in the sense that the poor are entitled to it. Almsgiving is more than justice: it is love that gives value to almsgiving and everything (1 Cor 13:3). Without love, almsgiving may be unjust, for it does not make people involved equal; charity does (José MarÃa Cabodevilla).

Authentic almsgiving is what is called formal almsgiving. There is material almsgiving and formal almsgiving. Giving to others in need without love is merely material but not formal or authentic almsgiving: “Almsgiving can be materially without charity, but to give alms formally, that is for God’s sake, with delight and readiness, and altogether as one ought, is not possible without charity†as love of God and neighbor (St. Thomas Aquinas).

Almsgiving is more than justice: it is love that gives value to almsgiving and everything (1 Cor 13:3). Without love, almsgiving may be unjust, for it does not make people involved equal; charity does (J. M. Cabodevilla).

Not giving alms when one can give is a source of condemnation (cf. Mt 25:41-43). We read in CCC: “Our Lord warns us that we shall be separated from him if we fail to meet the serious needs of the poor and the little ones who are his brethren†(CCC 1033; cf. Mt 25:31-46). The Second Plenary Council of the Philippines keeps telling us: “Eternal salvation depend on the living out of a love of preference for the poor because the poor and needy bear the privileged presence of Christ†(PCPII, 312)

In case of real need, corporal need is more important than spiritual need, which is generally more important: “a man in hunger is to be fed rather than instructed, and for a needy man money is better than philosophy, although the latter is better.†Love of neighbor, St. Thomas adds, implies beneficence and almsgiving, “for love of neighbor requires not only that we should be our neighbors’ well-wishers, but also his well-doers.â€

The classical theory of charity and mercy may appears as more concerned with the individual person than with the social order or disorder. Hence, almsgiving may be used as a cover up for injustice. Of course, almsgiving as a pathway of mercy cannot be unjust for it necessarily presupposes justice. Today more than yesterday, we speak of almsgiving not only to a person but also to a needy poor people, an ethnic group, the poor, the refugees, and the excluded from the banquet of life. Corporate almsgiving – donations -, or the Church’ s Caritas are much needed, irreplaceable in our world, and the rich nations are obliged to share with the poor ones as taught by the social doctrine of the Church (cf. Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, GS, 69; Paul VI, Populorum Progressio, PP, 23, 26, 43). In this context, excessive spending and squandering are sins (CCC, 2409). Religious men and women are asked by their vow of poverty to practice a simple life style, a life comparable to the life of the middle class – and not higher. “Let us live simply so that others may simply live†(Canadian Bishops).

Moreover, each one of us always needs to give something to the poor: to concrete individual poor persons. In November 2013, Pope Francis said to the religious and all: “Sometime of real contact with the poor is necessary.â€

Compassionate love urges Christians and all humans to “loving the unlovely, the unlovable, the least, the lost, and the last.†Mercy is not only sharing with the materially poor, although this aspect is much underlined, but also for all others in need, especially those in urgent need.

The merciful Jesus hopes to be able to tell you and me after crossing the bridge that links this life and the afterlife: “Come…, take as your heritage the kingdom prepared for you… For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you made me welcome, lacking clothes and you clothed me … “Why, Lord?†Because “In so far as you did this to one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did it to me†(Mt 25:34-40). I remember the words of Pope Francis during his visit to the Philippines (January 2015): “Our treatment of the poor is the criterion on which each one of us will be judged.â€

Words to ponder:

He who takes the clothes from a man is a thief. He who does not clothe the indigent, when he can, does he deserve another name but thief? The bread that you keep belongs to the hungry; to the naked, the coat that you hide in your coffers; to the shoeless, the shoes that are dusty at your home; to the destitute, the silver that you hide. In brief, you offend all those who can be helped by you (St. Basil the Great).

Â